Liquid inoculants for soybean and pulse crops are an effective method to apply nitrogen-fixing bacteria to seed prior to planting. Each inoculant is formulated specifically for the type of bacteria it contains to allow them to survive on the seed of their specific crop. The length of time they survive on-seed can vary between inoculants and the type of bacteria. This is known as the on-seed window of an inoculant. But what exactly does “on-seed window” mean? How is it determined? And why is it relevant to farmers?

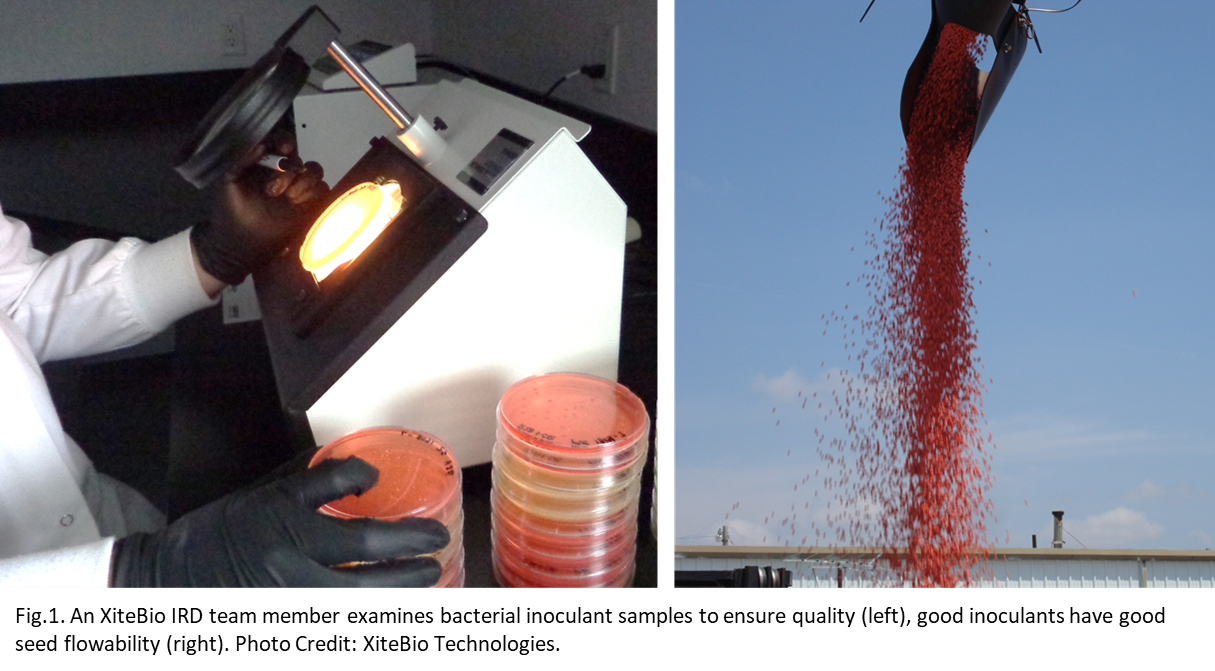

Liquid inoculants (or other formulation) generally contain few millions to billions of bacteria or colony forming units (cfu) per milliliter. This is to ensure that each individual seed will be treated with enough cfu to achieve proper nodulation. The ideal number required is different for each crop. The length of time inoculated seed will maintain this minimum number is referred to as the “on-seed window”. For example, the minimum number recommended for proper soybean nodulation is 100,000 cfu per seed (1). Using that number, inoculant manufacturers can test how long their inoculant will remain above the threshold after being applied to seed. For example, XiteBio® SoyRhizo® was lab tested continuously to determine an on-seed window of 90 days. This gives the user confidence that the inoculant will effectively perform within that time period.

Bacteria are living organisms and need resources to survive, and over time those resources get used up and the number of live bacteria remaining on the seed becomes less. Beyond the on-seed window, the number of cfu begins to decrease and drop below the threshold, impacting the performance of the inoculant. Some types of bacteria are more resilient than others, so the on-seed window can vary greatly between inoculants (2). There are several factors that contribute to the survivability of inoculant bacteria on seed, including available nutrients, moisture availability, interactions with other microbes, and tolerance of other seed treatment chemicals i.e. pesticides (3,4). Of these factors, compatibility with other seed treatments can have the strongest influence since some products are more stressful on bacteria than others. Proper testing of inoculant-seed treatment compatibility is critical to the success of inoculated crops. Click the following links to view compatibility information for XiteBio® SoyRhizo® and XiteBio® PulseRhizo®.

You may ask: if one product has a longer window than another, is it better? The answer: not necessarily. A longer on-seed window does not guarantee that a product is more likely to lead to successful inoculation, or that by using a product with a longer time on-seed you will yield better results. On-seed window and effectiveness are not correlated directly, and often a longer window can be misleading. As mentioned earlier, the longer the bacteria spend on the seed, the lower their population becomes (due to morbidity of bacteria). This is why lab testing is important when verifying the on-seed window of an inoculant. A certain number of bacteria are required/recommended to ensure successful nodulation, so the more your populations drop below this number the less likely your inoculation will have effective results.

Remember that your manufacturer’s storage instructions still apply to your treated seed the same as they apply to the inoculant before application. It is well known that bacterial survival is extended in lower temperatures (i.e. 4°C) by reducing their metabolic activity, but this is not always an option in real life, and preserving bacterial life at ambient seed storage conditions must be met to be viable in the mainstream agricultural market (5). Harmful environmental factors such as sunlight and freezing temperatures will still harm the bacteria on your seed during seed storage, so make sure you follow these recommendations until the seed is in the ground.

References:

1) Weaver, R., Frederick, L. 1972. A new technique for most probable number count of rhizobia. Plant and Soil, 1972, 36, 219-222.

2) Deaker, R., Hartley, E., Gemell, G. 2012. Conditions Affecting Shelf-Life of Inoculated Legume Seed. Agriculture, 2012, 2, 38-51; doi:10.3390/agriculture2010038.

3) Killham, K. 1994. Soil Ecology. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. P. 184-185.

4) Hartley, E., Gemell, G., Deaker, R. 2012. Some factors that contribute to poor survival of rhizobia on preinoculated legume seed. Crop & Pasture Science, 2012, 63, 858–865.

5) O’Callaghan, M. 2016. Microbial inoculation of seed for improved crop performance: issues and opportunities. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol (2016) 100:5729–5746.